2010 Season in Review: Javier Vazquez

The late ’90s Yankee dynasty was awash in pitching. Whether it was , , , , or , from 1996 to 2000 the Yankee rotation was stacked with excellent starting pitchers who excelled in the postseason. Unfortunately, only one of those players was homegrown. The rest were imported, and therefore old. As Larry pointed out on Monday, by the time the 2004 season began the once mighty pitching staff had crumbled away, mostly due to age, and in the case of Pettitte, bad business decisions.

This also exposed the basic risk of importing any players, pitchers or otherwise. Sometimes you sign El Duque for $12 million. Other times you trade Nick Johnson for . It may all seem like ancient history to Yankee fans, but back in 2004 Home Run Javy was a 27-year-old stud who had reeled off four consecutive strong seasons in Montreal. Hurt or otherwise, Javy had a terrible second half in pinstripes in his debut Yankee season that culminated in serving up a grand slam to in Game Seven of the 2004 ALCS, and he was promptly run out of town with a choker label on his forehead.

Most Yankee fans were content to forget about Vazquez after he was gone. Vazquez, on the other hand, went back to being a reliable pitcher. In the five seasons between 2005 and 2009 Javy never posted an ERA+ lower than 98 and broke 200 innings pitched each season. In 2009, Javy pitched 219.1 innings of 143 ERA+ baseball in Atlanta, his best season ever.

The Yankees, meanwhile, have never stopped needing pitching since 2003. Try as the team might to add or draft talented pitchers, the Bombers have perennially been one or two arms short. In 2009, the team overcame that to win the World Series, but a repeat trip seemed unlikely if the team couldn’t add another starter, preferably a proven innings eater who could take pressure off the bullpen. was the best free agent available. He was too expensive, but Vazquez was available for very little in trade. The rest is history, and a table of season splits not suitable for the faint-hearted:

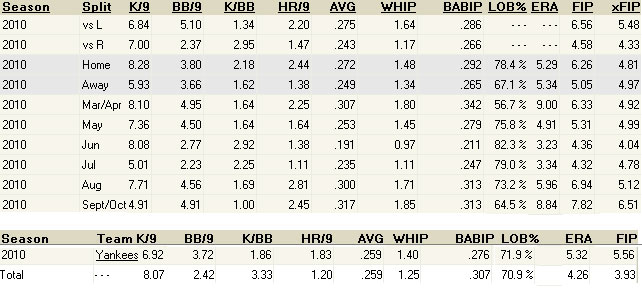

Vazquez’ season has a clear u-shape. He was miserable out of the gate. He pitched as bad in April as a pitcher can, giving up too many walks, hits, runs, doubles, homers, everything. Then, he actually got better. His numbers were poor but not terrible in May, while in June and July it actually looked as is if Vazquez was going to overcome his execrable start and put together an reasonable season. Then, the wheels fell off in August and September. Javy was far worse in August than he was in May, and he was almost as bad in September as he was in April. The net effect was an awful season of two good months sandwiched between four awful months.

2010 was arguably Javy’s worst professional season since 1998, when Vazquez was a 22-year-old rookie. His ERA of 5.32 was his worst since 1998. His ERA+ of 80 was replacement level, and his worst since 1998. His WHIP of 1.398 was not his worst since 1998, only his worst since 2000. His strikeout rate of 6.9 (believe it or not Vazquez is a strikeout pitcher) was also not his worst since 1998, but it was close, being his worst since 2000. Most importantly, his innings total, the primary reason the Yankees traded for him, was a measly 157.1, the first time he didn’t pitch at least 198 innings since 1999. In sum, Javy was awful, bad for a bWAR of 0.0 and you have to go all the way back to his cup-of-coffee seasons to find a time when he was this comparably terrible.

Javy throws four pitches: a fastball, a slider, a curveball and a changeup. According to Fangraphs each of those pitches rated above average in 2009, at 12.7, 3.0, 17.2 and 10.7 runs above average, respectively. In 2010, however, each pitch regressed to rating below average. Seriously. Each pitch. His fastball fell to -3.5, his slider to -4.0, his curve to -3.6 and his change to -0.7. The man went from having four plus pitches to four negative pitches in one season. You can’t make this stuff up.

The sports media suggested the problem was Javy’s lack of velocity. There may be truth to this. Not only did Javy go through a dead arm period in August, but his fastball and slider lost noticeable velocity (his other two pitches had the same speed). His fastball went from averaging 91.1 mph to 88.7 mph and his slider went from 83.9 mph to 82.5 mph.

This may have been enough to make Vazquez more vulnerable. He never had plus velocity stuff to begin with, but he managed to strike a lot of batters out. To do this, at least from what I observed in 2010, he needs horizontal movement on his pitches and he must keep them down in the zone. The drop in speed may have been responsible for Vazquez losing his swing-and-miss stuff. At the very least, whether or not it was because he lost speed, he definitely lost the swing-and-miss stuff. His contact rates were up across the board, both in the zone and out. A loss of velocity is as good an explanation for this as any other.

Baseball prognosticators often ask if a specific player has what it takes to make it in New York playing for the Yankees. The assumption is that the perfect storm of the New York media and the intensity of playing in the Bronx’s win-at-all-costs pressure cooker is more than specific players can handle, players like Randy Johnson, (from 2004 to 2008), and, most notoriously, .

I’ve always maintained this was nonsense. These are professional athletes who faced far more pressure breaking into the Major Leagues than they do once they’re established enough to get on the Yankees’ radar. Johnson was old. A-Rod was never actually a choker. But Vazquez? We may be about to find out. Javy is a free agent. He’s also earned about $80 million in his career. If he is willing to sign for a one-year, cheap deal — which is all he’ll be offered — he may pitch again in the Majors. At only 34 years old, Vazquez shouldn’t be done physically. If he regains form pitching away from the five boroughs then we may know for certain if some players — specifically the es of the world — just can’t cut it in the Bronx.

-

LIKE TYA ON FACEBOOK

-

Recent Activity

Recent Posts

- From prospect to pitcher: The Ivan Nova story

- Montgomery = Robertson?

- Mark Teixeira Is Still Powerless (And It’s Not OK Anymore)

- Yankees getting extra strikes

- Yankees Too Old For The Young Royals, Still Win 8-3

- Game 44: Let’s Go Streaking

- Buck Has Orioles Flying High, but Can They Rule the Roost? (History Says Yes)

- For Hughes: Regression, or Improvement?

- Analyzing Hughes’ May Turnaround

- 2012 looking like 2010 for Swisher, excepting the results

-

Authors

Twitter

* TYA Twitter -

* EJ Fagan -

* Matt Imbrogno -

* William J. -

* Larry Koestler-

* Moshe Mandel -

* Sean P. -

* Eric Schultz -

* Matt Warden -

-

Most poker sites open to US players also provide online casinos accepting USA players. A good example of this is BetOnline.com, where you can play 3D casino games, bet on sports or play poker from anywhere in the United States.

-

Other Links

-

Blogroll

Blogs

- An A-Blog for A-Rod

- Beat of the Bronx

- Bronx Banter

- Bronx Baseball Daily

- Bronx Brains

- Don't Bring in the Lefty

- Fack Youk

- It's About The Money

- iYankees

- Lady Loves Pinstripes

- Lenny's Yankees

- New Stadium Insider

- No Maas

- Pinstripe Alley

- Pinstripe Mystique

- Pinstriped Bible

- River Ave. Blues

- RLYW

- Steven Goldman

- The Captain's Blog

- The Girl Who Loved Andy Pettitte

- The Greedy Pinstripes

- This Purist Bleeds Pinstripes

- Value Over Replacement Grit

- WasWatching

- Yankee Source

- Yankeeist

- Yankees Blog | ESPN New York

- Yankees Fans Unite

- YFSF

- You Can't Predict Baseball

- Zell's Pinstripe Blog

Writers

- Bats (NYT)

- Blogging the Bombers (Feinsand)

- Bombers Beat

- Buster Olney

- E-Boland

- Jack Curry

- Joe Posnanski

- Joel Sherman

- Jon Heyman

- Keith Law

- Ken Davidoff

- Ken Rosenthal

- LoHud Yankees Blog

- Marc Carig

- Tim Marchman

- Tom Verducci

Resources

- Baseball Analysts

- Baseball Musings

- Baseball Prospectus

- Baseball Think Factory

- Baseball-Intellect

- Baseball-Reference

- BBTF Baseball Primer

- Beyond the Box Score

- Brooks Baseball

- Cot's Baseball Contracts

- ESPN's MLB Stats & Info Blog

- ESPN's SweetSpot Blog

- FanGraphs

- Joe Lefkowitz's PitchFX Tool

- Minor League Ball

- MLB Trade Rumors

- NYMag.com's Sports Section

- TexasLeaguers.com

- THE BOOK

- The Hardball Times

- The Official Site of The New York Yankees

- The Wall Street Journal's Daily Fix Sports Blog

- YESNetwork.com

-

Site Organization

Categories

Tags

A.J. Burnett ALCS Alex Rodriguez Andy Pettitte Baltimore Orioles Bartolo Colon Boston Red Sox Brett Gardner Brian Cashman Bullpen CC Sabathia Chien-Ming Wang Cliff Lee Curtis Granderson David Robertson Dellin Betances Derek Jeter Francisco Cervelli Freddy Garcia Game Recap Ivan Nova Javier Vazquez Jesus Montero Joba Chamberlain Joe Girardi Johnny Damon Jorge Posada Manny Banuelos Mariano Rivera Mark Teixeira Melky Cabrera Michael Pineda Minnesota Twins New York New York Yankees Nick Johnson Nick Swisher Phil Hughes Prospects Red Sox Robinson Cano Russell Martin Statistical analysis Tampa Bay Rays Yankees -

Site Stats

Recent Comments